Today, let’s talk about two of Twitter’s ongoing efforts to make itself more governable — and whether, eventually, those efforts are bound to conflict.

This week I attended a briefing organized by the company to talk about its efforts to fight misinformation. It was a timely discussion: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has put us all on high alert for dangerous falsehoods promulgating quickly on social networks, and Twitter has historically struggled to contain them.

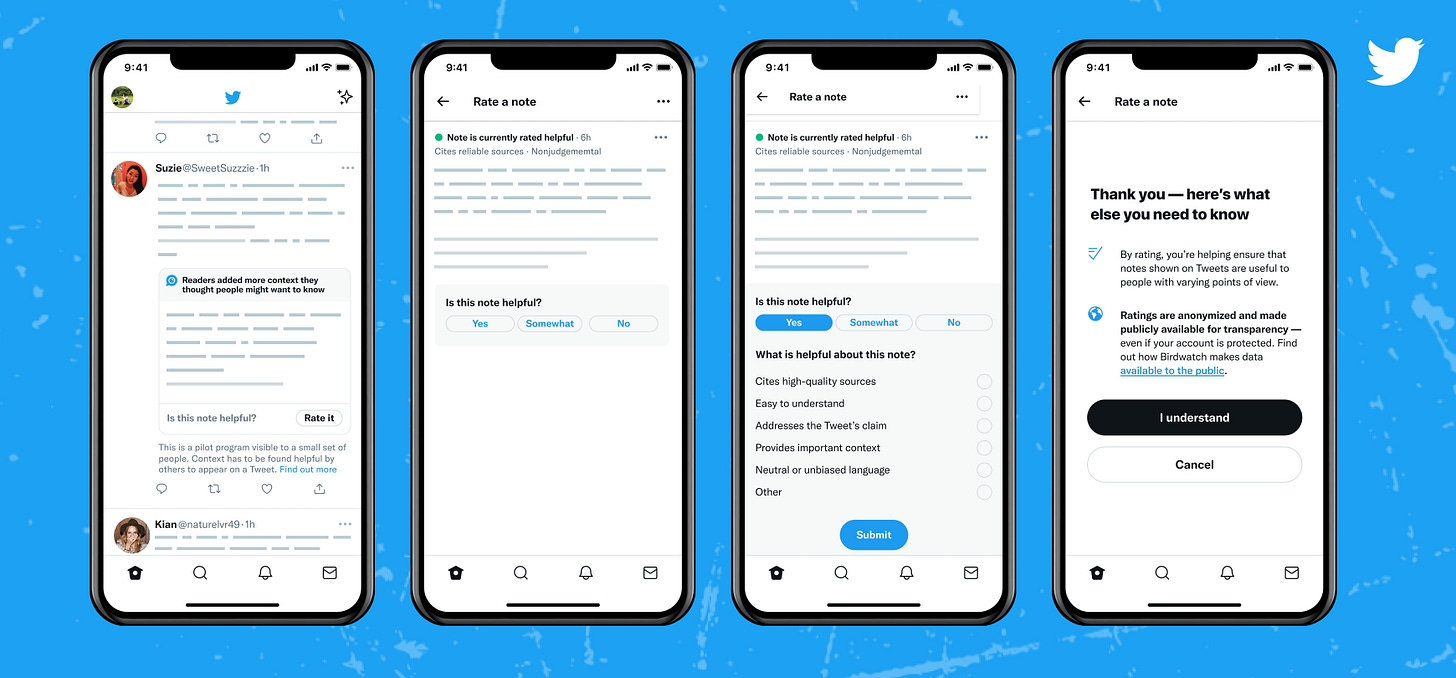

In January of last year, the company announced a novel experiment to rein in some of those misleading tweets. The effort, called Birdwatch, allows volunteer users to flag posts they believe to be misleading and add notes that describe why. A pilot group of 10,000 users was granted the ability to flag tweets, write notes, and rate the helpfulness of others’ contributions.

Since then, Birdwatch has flown mostly under the radar. An article in the Washington Post this week suggested why: test users simply haven’t been using Birdwatch very much. Here are Will Oremus and Jeremy B. Merrill:

A Washington Post analysis of data that Twitter publishes on Birdwatch found that contributors were flagging about 43 tweets per day in 2022 before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a microscopic fraction of the total number of tweets on the service and probably a tiny sliver of the potentially misleading ones. That’s down from about 57 tweets per day in 2021, though the number ticked upward on the day Russia’s invasion began last week, when Birdwatch users flagged 156 tweets. (Data after Thursday wasn’t available.) […]

Its data indicates that just 359 contributors had flagged tweets in 2022, as of Thursday. For perspective, Twitter reports that it is used by 217 million people worldwide each day.

That does seem like a slow start. But on Thursday, Twitter announced plans to accelerate Birdwatch’s development. The company will now expand the number of participants beyond the original sample, showing Birdwatch notes directly on disputed tweets, and allowing more people to rate notes according to how helpful they are.

The expansion came after the majority of testers said they found Birdwatch notes helpful, especially ones that had been rated highly by volunteers, said Keith Coleman, vice president of product at Twitter. Surveys showed people are 20 to 40 percent less likely to agree with tweets identified as misleading after reading Birdwatch notes, he said, giving the company confidence in the product’s potential.

How does Twitter decide which notes to show? It requires lots of data from volunteers, Coleman said. To be confident that a note is helpful, Twitter wants to see it marked as helpful by people who have disagreed about the helpfulness of other notes. The past year has been spent building that system out, collecting that data, and testing it in the wild.

Twitter has made other key changes along the way: letting people use pseudonyms on Birdwatch instead of their Twitter handles, for example, after research indicated that doing so made their ratings less partisan. (It’s easier to be a contrarian when your in-group won’t see your heterodox views.) It also now informs volunteers when their ratings are marked as helpful, and encourages them to provide sources for their claims.

And to get an independent view of Birdwatch, Twitter has also set of a partnership with the Associated Press and Reuters to assess the qualify of volunteers’ fact-checking. (So far, it seems to be pretty good, Twitter says.)

The company has taken other steps to reduce the spread of misinformation, redesigning the user reporting flow and the labels for misleading tweets. It’s also rolling out labels for state-affiliated media like Russia’s RT and Sputnik, signaling to users that they may be unwittingly spreading propaganda.

We’re fortunate that, in the early days of Russia’s war on Ukraine, misinformation has played only a limited role: no one can credibly dispute that this is an unprovoked attack on democracy, and Russia’s efforts to advance its own narrative have been feeble at best. (For wont of facts to check, some reporters have now turned to questioning whether Ukraine might be exaggerating stories about some of its heroes.)

But the consequences of misinformation go well beyond the war, and include high-stakes conversation about COVID-19, vaccines, and elections. The infrastructure Twitter is building now, if successful, should serve as a bulwark against more successful and dangerous propaganda campaigns in the future.

That is, if another effort at Twitter doesn’t upend them entirely.

I’m talking here about Project Bluesky, Twitter’s effort to reimagine itself as a decentralized protocol. More than two years into development, Bluesky has little to show for itself beyond a white paper, a leader, and an active Discord server. As such, it can be hard to think through the implications of a decentralized Twitter, or even to understand what “decentralized” means in this context.

But in a new story in the New York Times, Kate Conger updates us on Bluesky’s aims and its progress. She writes:

A decentralized Twitter could take years to emerge and might look much the same as it does today. But it could allow users to set moderation rules for their own communities and ease the pressure Twitter faces from lawmakers over how it moderates content. It might also open new revenue streams for the company. […]

The Bluesky project would eventually allow for the creation of new curation algorithms, which would show tweets at the top of users’ timelines that differed from what Twitter’s own algorithm showed. It would give users more choice about the kinds of content they saw, Mr. Dorsey said, and could allow Twitter to interoperate with other social media services.

There are lots of “coulds” and “woulds,” in here, due to the still underbaked nature of the project, and few would be surprised if Twitter abandons the entire effort someday after finding it to be unworkable.

At the same time, as the story makes clear, decentralization is a high priority for Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal. As such, it’s worth thinking through what efforts to “allow users to set moderation rules for their own communities” would mean for Twitter, and for efforts like Birdwatch.

A fact-checking program that relies on contributions from average users relies heavily on the centralized nature of the service. Drawing from hundreds of millions of users, Twitter can find volunteers to rate notes, generate heaps of data to improve the service, and show top-rated fact checks to the maximum number of people. Everyone’s individual Twitter timeline will still look different, but the existence of a single centralized service means that fact-checking efforts can reach all of them.

Now imagine a world where Twitter is simply one client of a decentralized protocol, and that big chunks of the user base begin moving to other clients: one with a right-wing bent and very few moderation rules; another that offers only a reverse-chronological timeline. In this world, would it be mandatory for every node on the protocol to enable Birdwatch-style fact-checking? Would fact-checks extend beyond whatever node posts first appeared on? Or would the protocol adopt the laissez-faire, anti-censorship attitude of most web3 projects to date?

We already live in a world where the people most likely to seek out fact-checks are some of the least likely to need them. If Birdwatch becomes a module that moderators can choose to add or remove from their decentralized instance of Twitter, it would probably be much less effective.

The good news is that Twitter still has plenty of time to figure it out. Birdwatch, like Bluesky, is still effectively in its infancy. And we have good models for how to build decentralized systems that retain a core of centralized services: it’s how Google operates Android, for example.

But there’s also a risk that these projects could proceed down separate, incompatible paths. It would be unfortunate if, in its zeal to embrace the benefits of decentralization, Twitter forgot about all the good that centralized services can do.

Elsewhere in Twitter: Its offices will reopen globally on March 15.

Corrections

Thanks to everyone who pointed out that it’s attorneys general, not attorney generals, as I put it in the headline of yesterday’s post. Blame the fog of war!

War

ICANN rejected Ukraine’s request to remove Russia from the global internet. (Brian Fung / CNN)

RT America laid off its entire staff. Is Tucker Carlson hiring? (Oliver Darcy / CNN)

Spotify closed its Russia office and removed all shows from RT and Sputnik. (Todd Spangler / Variety)

Reddit banned links to Russian state media across its entire site. (Jon Fingas / Engadget)

The United Kingdom asked Meta to ban RT and Sputnik, even though the UK hasn’t even yet banned them itself. (Jennifer Ryan and Thomas Seal / Bloomberg)

RT and Sputnik have been welcomed on at least one platform, though: the right-wing YouTube alternative Rumble. (Sheila Dang / Reuters)

In a reversal, Apple Maps and Weather now show Crimea as part of Ukraine, at least outside of Russia. Huge congrats to Crimea. (Filipe Espósito / 9to5Mac)

TripAdvisor and Google Maps blocked reviews of some Russian listings after users flooded them with political messages. (Katie Deighton / Wall Street Journal)

Ukraine is posting photos and videos of captured and killed Russian soldiers across Telegram, Twitter, and YouTube. Experts say the move could violate the Geneva Convention. (Drew Harwell and Mary Ilyushina / Washington Post)

Ukraine has now received more than $50 million in cryptocurrency donations. More than 90,000 wallets have contributed to date. (Scott Chipolina / Decrypt)

Ukraine is spending donated money on “critical supplies like drones, bulletproof vests, heat-sensitive goggles and gasoline, from both state actors and the private sector.” (Nitasha Tiku and Jeremy B. Merrill / Washington Post)

Ukraine canceled a planned token airdrop, though, saying it would sell NFTs instead. (Andrew Rummer and Tim Copeland / The Block)

A look at Ukraine’s propaganda efforts, including the likely mythical “Ghost of Kyiv” fighter pilot and falsely reporting that the soldiers who confronted a Russian warship on Snake Island had died. (Stuart A. Thompson and Davey Alba / New York Times)

The Github repo for React, an open source library maintained by Facebook, was spammed by anti-Ukrainian and anti-American comments in English and Mandarin. (Joseph Cox / Vice)

Ukraine called on gaming companies to temporarily block all accounts in Russia and Belarus. Poland's CD Projekt Red (makers of The Witcher series and Cyberpunk 2077) took them up on the request. (Kyle Orland / Ars Technica)

Senators are pressing Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to explain how the administration will ensure that cryptocurrency companies enforce sanctions against Russia. (Emily Flitter and David Yaffe-Bellany / New York Times)

Hackers breached the website of the Russian Space Research Institute. (Joseph Cox / Vice)

Industry

Amazon-owned Twitch has lost six top executives since January amid complaints it has lost focus on creators. (Cecilia D'Anastasio / Bloomberg)

Twitch said it would ban people for spreading misinformation, in a new move for the platform. The policy prohibits spreading falsehoods about medical treatments, COVID-19 vaccines, and elections, among other things. (Kellen Browning / New York Times)

The Federal Trade Commission has until mid-March to decide whether to intervene to stop Amazon from acquiring MGM. (Joe Flint, Dana Mattioli and Brent Kendall / Wall Street Journal)

Crypto wallet MetaMask became suddenly inaccessible in Venezuela, possibly due to US sanctions. (MK Manoylov / The Block)

And in an apparently related story, OpenSea banned users in Iran. (Eli Tan / CoinDesk)

The US surgeon general formally requested that social networks submit information about the scale of COVID-19 misinformation on their platforms. (Davey Alba / New York Times)

Those good tweets

Talk to me

Send me tips, comments, questions, and Birdwatch notes: casey@platformer.news.

Birdwatch-style explicit fact-checking might have some value, but obviously has issues with participation. Reliance on implicit user feedback based on understanding organic reactions -- and the reputation of who they come from -- could crowdsource valuable quality signals from a far larger universe. Jeff Allen suggested such an approach when at Facebook, building on Google's PageRank strategy (https://ucm.teleshuttle.com/2021/10/the-best-idea-for-fixing-facebook-from.html), as had I. One could supplement the other.